Gérard Maurice

Professeur des Facultés de Droit

Ex: https://metamag.fr

Quand il n’est pas devant son écran, Thierry M. adore se promener dans la ville. Il va au vidéo-café lorsque son argent de poche le lui permet. Il ne se lasse pas de regarder les panneaux géants de cristaux liquides sur lesquelles s’affichent les publicités les plus folles et qu’on peut voir en plein soleil comme si on était chez soi dans la pénombre devant son écran.

La ville est ainsi jalonnée d’écrans qui scintillent en permanence pour vanter le Coca-cola, les produits Pioneer ou les voitures japonaises. Entre deux publicités passent des clips vidéos, et il n’est pas rare de voir dix ou quinze jeunes assemblées devant ces sucettes géantes.

Lorsqu’on demande à Thierry M. ce qu’il veut plus tard, il répond invariablement : « avoir du temps » Pour quoi faire ? Thierry ne le sait pas, et ne veut pas le savoir, même si au fond de lui une petite voie inquiète lui renvoie l’écho de sa solitude.

Car Thierry vit désespérément seul. Hanté par les images extérieures, il a fini par perdre peu à peu la sienne. Il n’a pas de besoins particuliers : les images lui servent de substitut. Il n’éprouve pas de désir d’échanger avec extérieur : il est l’extérieur.

Deux figures de la société individualiste médiatique peuvent ouvrir mon propos : M. M, cadre commercial et M. Z, le tolérant.

Ses goûts sont ceux du marché corrigé des variations saisonnières, il ne conçoit rien au-delà de son opinion, il ne voit rien au dessus de la cohue du « moi… ».

Tout idéal lui paraît un danger pour la démocratie, toute valeur permanente un frein à la liberté… tout souci de l’avenir une menace envers l’instant présent…

Ce garçon est un échantillon de ce siècle dominé par un système économique, social, mental dont la logique est d’éradiquer le spirituel.

La société occidentale réduit nos désirs à l’horizon matériel, échappent à notre vue non seulement le spirituel, l’âme des choses mais la simple notion commune du bien et du mal.

Or, la fin du XXème siècle et le début du XXIème nous réduit à la matière et au mécanisme.

Elle menace de rendre le XXIème siècle doublement orphelin du spirituel, elle efface la notion d’âme et de désir éternel.

Elle nous installe dans le culte du moment présent, ce qui coupe le mouvement même de la civilisation.

Car est spirituel car possède l’âme, ce qui parvient à échapper à l’absurde et surtout au temps et à son usure, c’est ce qui surmonte la mort de l’individu et celle des civilisations, ces instants d’éternité qui incarnent l’histoire.

Quelles portes ouvrent ces instants d’histoire, le courage et la fraternité ?

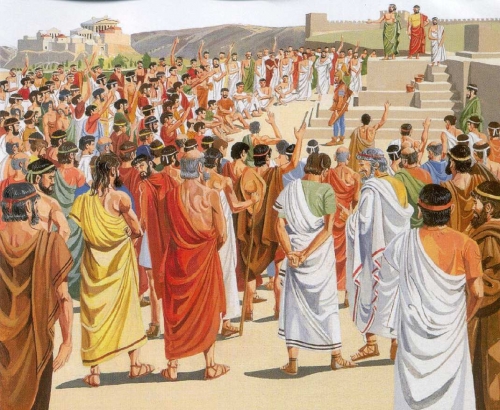

La cité antique organisait ces instants en conjuguant quatre forces : le citoyen / hoplite, la provenance qui structurait l’appartenance, l’éternité / gloire, l’histoire / pérennité.

Il appartenait aux héros d’incarner le génie et le destin de la cité … Ils façonnaient l’histoire et l’exemple : Hector, Achille, Léonidas… toute l’Europe est déjà dans l’Eliade.

A l’évidence, la cité moderne ne conjugue pas les mêmes forces. Histoire / Présentisme, Citoyen / nomade, Provenance / déracinement, Eternité / relativisme

Le résultat est perceptible, il est celui d’une grande déprime, suicide, peur de la mort, angoisse, hédonisme marquent l’espace public. La pub idéologie ne parvient plus à contenir les frustrations (le club Méditerranée).

La France, par son nombre de suicides, arrive dans le peloton de tête des pays européens… ce n’est plus un hasard mais une véritable anomie.

Darkheim écrivait « la vie n’est tolérable que si on lui aperçoit quelque raison d’être, que si elle a un but et qui en vaille la peine. Or l’individu à lui seul n’est pas une fin suffisante ».

Le sens de la voie, pour être véritablement intériorisé par les sujets, doit être envisagé collectivement.

La racine fondamentale de cet effondrement doit être recherché dans l’effritement des rapports communautaires et à la déperdition du bien commune.

Dès lors que les hommes ne peuvent partager un ensemble de valeurs, aucune action collective n’est possible.

Les Grecs avaient eu le sens de l’harmonie, équilibre des contraires et organisaient le chaos.

Le vide contemporain précipite nos concitoyens dans une obsession de survie immédiate. Plus rien ne compte sinon un surcroît de vie.

Une éthique d’auto préservation se met en place, fleurissent alors les différentes techniques d’épanouissement de soi, de la méditation tantrique en passant par le Feng Shi et pour les plus fortunés par le coachting.

L’aspiration dominante est la performance physique et psychologique…

Ce survivalisme, pour reprendre le mot de Christopher Lash, prend racine « dans l’expérience subjective du vide et de l’isolement ».

De son côté Gail Sheehy écrit « l’idéologie actuelle semble un mélange de désir de survie, de volonté de renaissance et de cynisme individuel ».

Cependant ce survivalisme se mue en peur pathologique de la mort.

L’effondrement démographique entraîne de son côté un amenuisement du lien entre générations, tandis que l’absolutisme du présent efface tout sacrifice pour le futur.

De manière pathétique, la valeur refuge est assurée par une prothèse : la télévision.

Cette grande usine de rêve sert de tout à bon nombre de nos concitoyens qui la subissent en moyenne 4 heures/jour, et qui s’abîment devant ce mur d’images comme les hommes troncs du film de Truffaut : Farenheint 45

Ainsi progressivement le destin de nos cités est dominé par la lute entre deux imaginaires, d’une part celui des machines à rêver avec leur incalculable puissance et d’autre part, ce qui peut exister en face de lui et qui n’est pas autre chose que l’héritage de la noblesse du monde… de l’aristocratie de pensée.

Nos cités sont désormais confrontées à la dictature du présent et aux batailles dans l’imaginaire.

I – LA DICTATURE DU PRÉSENT

La société a adopté les valeurs féminines.

De ce choix témoigne le primat de l’économie (3ème fonction) sur la politique ; le primat de la discussion sur la décision, le déclin de l’autorité au profit du dialogue ; la mise sur la place publique de la vie intime, la survalorisation de la parole de l’enfant, la vogue de l’humanitaire et de la charité médiatique, les problèmes de santé, du paraître, la diffusion des formes rondes, la sacralisation du mariage d’amour, la vague de l’idéologie victimaire, la multiplication des cellules de soutien psychologiques, le développement du marché de l’émotionnel et du compassionnel, une justice qui doit permettre la reconstruction des douleurs et non plus le jugement de la loi, la généralisation des valeurs du marché, de la transparence, de la mixité, du nomadisme, du flux et du reflux.

A une société raide, surplombante, verticale, se substitue une société liquide, de réseaux, de l’indistinction des rôles sociaux.

C’est le gonflement du « moi » et le « fonctionnalisme » qui l’emportent.

La dictature du présent c’est l’hypertrophie de l’intime et de l’utilitarisme.

L’hypertrophie de l’intime se manifeste par le gonflement du « moi » et par le primat de l’économie.

1. Le « moi » devient le centre de tout.

Il se complet dans l’immédiat et l’égolatrie. Le maître mot de l’immédiat, c’est l’urgence ;

Si l’on admet l’idée selon laquelle la temporalité d’une société s’ordonne autour d’un axe présent, passé, avenir, on note aujourd’hui une surcharge du présent au détriment à la fois du passé et de l’avenir.

Dans ce cadre, l’urgence est la traduction sociale de cette surcharge. Le temps est ainsi surchargé d’exigences inscrites dans la seule immédiateté. La montée en puissance du thème de l’urgence renforce la logique économique de l’immédiateté…

De surcroît toutes les politiques d’urgence tendant à se fonder non pas en raison mais en émotion, il en est ainsi du plan de lutte contre le chômage, pour l’emploi, contre les délocalisations, pour le Darfour…

Certes le motif d’action est difficilement récusable, mais son opérationnalité passe par un consensus émotif initial.

Ce traitement, en urgence, ajoute à la compression du temps que la mondialisation induit en termes technologiques et de marché.

Désormais, il ne s’agit plus de gagner de nouveaux espaces, car le monde est atteint dans toutes ses limites, mais il s’agit de gagner du temps.

Le temps devient une valeur marchande en soi. Cette hypertrophie de l’immédiat est accompagnée d’une hypertrophie des intimités.

La tendance au repli sur soi est renforcée par une vive méfiance, de nature paranoïaque, à l’égard de l’autorité et des communautés.

La moindre influence est vécu comme une intrusion insupportable.

C’est pourquoi l’adhésion à des héritages culturels ou à des traditions est jugée aliénante.

En fait, on constate depuis 40 ans un rejet forcené de toutes les figures d’ordre.

Or l’intériorisation de ces figures assurait à l’enfant et à l’adolescent un apprentissage, une assurance et une sécurité.

Le manque d’intériorisation génèrera un défaut de confiance en soi, des angoisses paradoxalement compensées par une survalorisation du moi.

L’individualisme contemporain est lié à un mouvement de frénésie et de « bougisme » porté par une sorte d’égolatrie et un rejet de toute verticalité au tradition.

L’adolescence ou le jeunisme se prolongent indéfiniment tandis que le sens collectif fait défaut.

Selon le mot d’Alain Ehrenberg : « l’individu souffrant a supplanté l’individu conquérant ».

On comprend dans ce cas que la démocratie ne soit plus veuve comme le mode d’expression d’un peuple conscient de son histoire et de son destin mais elle devient une manière individuelle de voir la vie, une façon de brandir nos goûts intimes et de réclamer que la cité nous aide à les satisfaire sans délai.

Le nouvel individu démocratique n’est pas un citoyen ancré dans l’histoire, c’est un consommateur flottant au gré des modes.

Il baigne dans l’impatience.

Son univers est celui de l’instantané commercial, achat sans délai (la pub), émotion minute (la télévision), le zéro distance.

Il se satisfait donc du primat de l’économie, bien plus il l’exige.

2. Cette enflure de l’économie alimente aussi l’hypertrophie de l’intime.

En effet, le primat de l’économie ramène la politique à la gestion des choses et transforme les droits de l’individu en créance économique.

Le totalitarisme économique a débouché sur la marchandisation généralisée, c’est-à-dire sur l’idée que tout ce qui est de l’ordre du désir ou du besoin peut être négocié.

Le modèle normatif devient celui du négociant.

Aristote écrivait « ceux qui croient que chef politique, chef royal, chef de famille, et maître des choses sont une seule et même notion, se trompent. Ils s’imaginent que les diverses formes d’autorité ne diffèrent que par le nombre de ceux qui y sont assujettis. En fait, il existe entre chaque autorité, une différence de nature ».

Marcel Henaff aujourd’hui dit la même chose lorsqu’il énonce « réduire la politique à une tâche de gestion économique, c’est oublier la fonction souveraine de reconnaissance publique des citoyens ».

Il est donc logique que l’individu vive sa relation au politique à travers de simples revendications matérielles, érigeant ses droits en un droit de tirage permanent sur le système conçu comme une sorte d’immense machine à « miam-miam ».

L’hypertrophie du droit au dépend du politique est une autre conséquence de la montée en puissance de la gestion fonctionnelle de l’espace public.

Car la dictature du présent ramenant tout à soi érige le « fonctionnalisme » en huile de rouage du marché.

Le triomphe du « fonctionnalisme » :

Ramener tout phénomène à son utilité ou à sa fonction réduit la cité à un agrégat et le citoyen à l’homme.

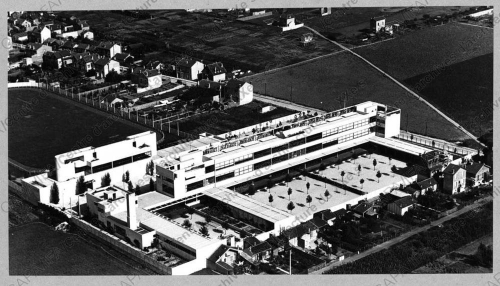

1. Le passage de la cité organique à forts liens communautaires et symboliques, à une cité fonctionnelle et « zonée » a littéralement privé les villes de leur âme.

C’est à coup sûr la charte d’Athènes, inspirée par Le Corbusier, qui a donné le coup de grâce à la cité-histoire.

La Charte d’Athènes introduit une vision mécanique de la ville et de l’urbanisme. Elle a expulsé l’histoire de ses vues, elle a choisi la rentabilité et l’anonymat. Les villes, découpées selon les fonctionnalités marchandes ont créé des lieux au ban qui sont des non villes, même les plus riches n’échappent pas à ce vide. Les nouveaux hameaux, les nouveaux villages n’ont pas plus d’âme… c’est Los angeles sur Seine, le « bonheur si je veux ».

Autrefois, les métiers structuraient la ville.

Le boucher, le tapissier, le boulanger avaient des modes de vie différents. Aujourd’hui, les modes de vie se sont indifférenciés, les quartiers deviennent plus ou moins identiques et on cherche vainement un paysage urbain. A part le centre historique qui pourrait évoquer un destin collectif.

La ville est devenue un pur système d’objets où des individus isolés se meuvent dans toutes les directions sans autre but que les flux de consommation et du spectacle.

A la communauté d’appartenance et d’histoire succède une communauté d’inquiétude et de mécontentement.

Ces barbaries à visage urbain où triomphent les tribus urbaines constituées de zombies acculturés, ayant pour modèles les noirs américains des ghettos de Los angeles, concourent à la destruction du politique qui a tenté désespérément de retourner à la base selon un principe illusoire « connaître au mieux et au plus près ce que veulent les gens ».

En réalité le remède est pire car l’action politique se trouve réduite à une société de services, ce qui conduit à exacerber les demandes individuelles au détriment du bien commun.

Le culte excessif de la proximité détruit l’intérêt général et favorise des réponses en forme de catalogue à la Prévert.

En réalité, ce qui se profile derrière tout cela c’est la destruction des distances symboliques.

Les petites phrases remplacent les discours… le débat sur les finalités a disparu, il n’y a plus de citoyens mais des activités citoyennes relevant de la morale.

2. Ici l’homme supplante le citoyen.

Il est pris en charge par le système qui affiche plusieurs figures : le politico technocrate, le gentil présentateur de télévision, le publicitaire.

Toutes concourent à lui décrire les mérites, de l’homme fonctionnel parfait, bronzé et ouvert.

Même Jacques Attali prophétise que la frontière s’amenuisera entre la personne et l’artefact, entre la vie sacrée et la vie utilitaire.

Tout cela doit déboucher sur un être « sans père, ni mère, sans antécédents, ni descendants, sans racine ni postérité, un nomade absolu ».

Nomade par la mentalité acquise, marquée par l’éphémère et l’inconséquence.

Dans son dernier ouvrage, il précise le contour de ce nomade qui sera un transhumain, citoyen planétaire.

Décidemment un nihilisme à peine déguisée habite le microscome.

C’set pourquoi le destin de nos cités assujetti par la dictature du présent, se jouera au cours d’une bataille dans l’imaginaire, parce que c’est là que se forgent et s’apprécient les représentants du monde.

II – LA BATAILLE DANS L’IMAGINAIRE

S’il est vrai que l’homme, animal culturel, ne vit pas le monde en direct, mais se le représente, à travers une grille d’interprétation dont la structure dépend de la culture de chaque peuple voire, des ensembles géoculturels, alors la bataille dans l’imaginaire relève de l’ordre du symbole.

A cette dictature du présent, de l’immédiat, de l’anonymat, du nomadisme, de la consommation de masse, de l’amnésie et du bonheur matériel à tout prix, que répondre si ce n’est d’invoquer non pas la fin de l’histoire mais le sursaut de l’histoire, d’y ajouter une volonté de différence, d’identité qui puisse interrompre un mouvement sans sens.

Le sursaut de l’histoire implique que soient « réunies certaines conditions et que soit affichées une ambition ».

Malraux, en 1965, dans un discours à l’Assemblée nationale, avait proféré des phrases terribles : « le futur sera dominé par l’Empire global, celui de l’audiovisuel, grande usine à rêve ».

Or nous sommes une civilisation qui devient vulnérable dans ses rêves car la technologie de l’image permet aux anciens domaines sinistres, ceux du sexe et du sang, de l’emporter sur le sacré et la mémoire.

Il ajoutera : « les dieux sont morts mais les diables sont biens vivants…. »

Le préalable à tout sursaut est donc de réintroduire de la perspective, de la distance, de l’histoire…

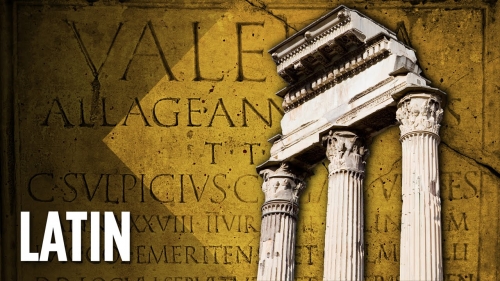

Enseigner à nouveau, voire en rendre une obligatoire, les langues anciennes dites inutiles, c’est en réalité réintroduire 4000 ans dans la mémoire des enfants qui se verront ainsi héritiers et non plus éphémères estomacs sur pattes.

A la société médiatique guidée par les lois de l’émotion, de la séduction, de la mode, de l’insignifiance, du gnan-gnan, il faut non pas opposer mais exiger en parallèle le retour de la démocratie originale, la démocratie directe.

Nous assistons à l’épuisement d’un modèle d’autorité surplombante où la décision est concentrée dans les mains d’un pouvoir d’en haut où le média est auto instrumentalisé pour légitimer le rôle d’un petit groupe d’hommes et de femmes en état de connivence.

Certes la démocratie directe, forme originelle de la démocratie, peut difficilement s’exercer sur un vaste territoire.

Toutefois cette remarque n’est pas rédhibitoire, car cette demande de démocratie directe que d’aucuns appellent démocratie participative, passe par un renforcement du local et de la mise en œuvre du principe de subsidiarité.

Il ne s’agit pas de faire participer des associations spontanées, sorte de quasi néo-soviets ou de jury populaires ; il faut rendre à chaque échelon des appartenances le droit de gérer en direct ce qui le concerne.

Rien n’interdit un mixage entre la démocratie directe et la démocratie représentative, il suffit de laisser à la première le droit de s’introduire dans le débat parlementaire ou d’assemblée locale par un droit d’initiative référendaire.

Quant au principe de subsidiarité, il s’inscrit naturellement dans une écriture politique fédérale.

Au fond la mondialisation, comme l’internationalisme de Jaurès, donne envie de plus de patrie charnelle pour mieux soutenir ceux des nôtres qui doivent guerroyer sur les fronts mouvants du marché.

Les conditions réunies permettent de bâtir une nouvelle ambition.

Cette ambition doit s’appuyer sur deux leviers, d’une part le retour de la liberté des anciens, d’autre part un choix holistique.

Benjamin Constant avait revendiqué le droit d’intimité contre le droit de participer à la vie de la cité.

Dans l’Antiquité, la liberté s’atteignait d’abord par la participation active et constante des citoyens à la vie publique.

Or pour les théoriciens libéraux, la liberté se conquiert dans la sphère privée, ce qui signifie que la liberté n’est plus ce que permet la politique mais ce qui lui est soustrait.

En d’autres termes, la liberté réside dans la garantie d’échapper à la sphère publique.

Elle ne relève plus de l’essence politique mais de l’existence personnelle.

Redonner aux citoyens le goût de privilégier l’espace public, c’est à tout coup les sortir d’une relation nécessairement mutilante car pour l’heure elle consiste à émettre des demandes dont la satisfaction ne peut être qu’aléatoire ou destructrice de l’intérêt général.

Cet espace public peut être approché par des individus comme par des communautés si par ailleurs on insiste sur le mode holistique.

Ce mode valorise la communauté et ne laisse plus l’individu seul et solitaire.

Le monde traditionnel ne livrait pas les personnes à elles-mêmes, les vieillards étaient pris en charge par les jeunes, les parents aidaient les enfants, la famille était une souche, l’honneur et l’hospitalité, le fondement de la relation sociale.

C’était l’application naturelle du don et du contre don, distinct du principe de l’échange.

Il faut l’avouer, il existe plus de pratiques sociales de ce type parmi les populations immigrées, ou encore dans les terres latines ou villageoises celtes que dans la ville de Paris où la canicule a fait plus de ravages qu’ailleurs.

Bref engager la bataille dans l’imaginaire, c’est engager dans le discours et la pratique sociale, le combat pour les appartenances.

Cette reconquête des appartenances ouvrir le débat sur l’identité comme fondement de l’âme de la cité, mais c’est aussi réintroduire une volonté pour le futur.

La demande d’identité est une demande antimoderne dans la mesure où la modernité n’a pas cessé d’étendre l’indistinction.

Le déblocage de l’histoire passe par l’écriture de nouvelles histoires, car l’identité n’est pas une substance mais une réalité dynamique qui réintroduit du temps.

D’ailleurs, les revendications identitaires fleurissent de toutes parts car elle dénonce cette injustice qui est le déni de reconnaissance des identités.

A l’exigence quantitative de redistribution des ressources se substitue l’exigence qualitative de la reconnaissance des appartenances.

L’identitarisme peut aboutir au meilleur comme au pire, il ne faut pas enfermer l’identité dans une forteresse, mais en faire un levier de connaissance de l’Autre qui n’a pas vocation à être un même.

Car comme l’a écrit Claude Imbert, « notre identité est atteinte par l’effondrement du civisme, par l’appauvrissement de la langue mais surtout par une homogénéisation technico-économique du monde qui généralise le non sens et qui rend chaque jour les hommes plus étrangers ».

Retrouver le sens du bien commun concourent à la singularité de la communauté et donc évite le repli sur soi.

Cette reconquête des appartenances permet enfin de réintroduire du futur, car retrouver sa mémoire c’est aussi rompre avec le présent et réenclencher la dynamique du passé, présent, futur.

En fait, le recours à l’histoire des appartenances n’est pas neutre, il permet aux acteurs de se reconnaître dans le passé et de se projeter pour dans le futur de pérennité et de destin.

Ce regard nous constitue à la fois comme sujets sociaux et comme acteurs de notre propre liberté. Certes la mémoire n’est jamais intégrale, le traitement symbolique de l’histoire est toujours subjectif mais l’indentification de la provenance peut donner un sens au futur. C’est désormais la condition primordiale de la reconnaissance des âmes collectives sans lesquelles la cité des hommes ne sera qu’un instant sans sens

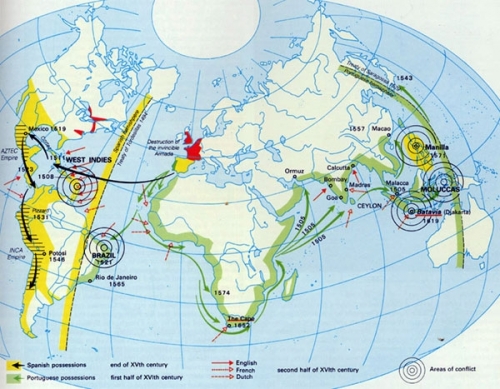

Maar het zijn protestanten in Noordwest-Europa die zich tot echte zeemachten ontwikkelen, doordat watergeuzen en piraten een primaire afhankelijkheid van de zee ontwikkelen. Het zullen uiteindelijk dan ook de Engelsen (en zij die als de Engelsen denken) zijn die de vrijgemaakte maritieme energieën beërven en het idee propageren dat de zee vrij is, dat de zee niemand toebehoort.Dat idee lijkt eerlijk genoeg, de zee is vrij dus van iedereen, niet waar? Maar als de open zee niemand toebehoort, geldt er uiteindelijk het recht van de sterkste. “De landoorlog heeft de tendens naar een open veldslag die beslissend is”, schrijft Schmitt. “In de zeeoorlog kan het natuurlijk ook tot een zeeslag komen, maar zijn kenmerkende middelen en methoden zijn beschieting en blokkade van vijandelijke kusten en confiscatie van vijandige en neutrale handelsschepen [..]. Het ligt in de aard van deze typerende middelen van de zeeoorlog, dat zij zich zowel tegen vechtenden als niet-vechtenden richten.”

Maar het zijn protestanten in Noordwest-Europa die zich tot echte zeemachten ontwikkelen, doordat watergeuzen en piraten een primaire afhankelijkheid van de zee ontwikkelen. Het zullen uiteindelijk dan ook de Engelsen (en zij die als de Engelsen denken) zijn die de vrijgemaakte maritieme energieën beërven en het idee propageren dat de zee vrij is, dat de zee niemand toebehoort.Dat idee lijkt eerlijk genoeg, de zee is vrij dus van iedereen, niet waar? Maar als de open zee niemand toebehoort, geldt er uiteindelijk het recht van de sterkste. “De landoorlog heeft de tendens naar een open veldslag die beslissend is”, schrijft Schmitt. “In de zeeoorlog kan het natuurlijk ook tot een zeeslag komen, maar zijn kenmerkende middelen en methoden zijn beschieting en blokkade van vijandelijke kusten en confiscatie van vijandige en neutrale handelsschepen [..]. Het ligt in de aard van deze typerende middelen van de zeeoorlog, dat zij zich zowel tegen vechtenden als niet-vechtenden richten.”

L'homme est au centre de l'univers selon Charbonneau, qui ouvre son texte de bien belle façon en affirmant qu'avant «l'acte divin, avant la pensée, il n'y a ni temps, ni espace : comme ils disparaîtront quand l'homme aura disparu dans le néant, ou en Dieu» (1). Si l'homme se trouve au centre d'une dramaturgie unissant l'espace et le temps, c'est qu'il a donc le pouvoir non seulement d'organiser ces derniers mais aussi, bien évidemment, de les déstructurer, comme l'illustre l'accélération du temps et le rapetissement de l'espace dont est victime notre époque car, «si nous savons faire silence en nous, nous pouvons sentir le sol qui nous a jusqu'ici portés vibrer sous le galop accéléré d'un temps qui se précipite», et comprendre que nous nous condamnons à vivre entassés dans un «univers concentrationnaire surpeuplé et surorganisé» (le terme concentrationnaire est de nouveau employé à la page 31, puis à la page 50), où l'espace à l'évidence mais aussi le temps nous manqueront, alors que nous nous disperserons «dans un vide illimité, dépourvu de bornes matérielles, autant que spirituelles».

L'homme est au centre de l'univers selon Charbonneau, qui ouvre son texte de bien belle façon en affirmant qu'avant «l'acte divin, avant la pensée, il n'y a ni temps, ni espace : comme ils disparaîtront quand l'homme aura disparu dans le néant, ou en Dieu» (1). Si l'homme se trouve au centre d'une dramaturgie unissant l'espace et le temps, c'est qu'il a donc le pouvoir non seulement d'organiser ces derniers mais aussi, bien évidemment, de les déstructurer, comme l'illustre l'accélération du temps et le rapetissement de l'espace dont est victime notre époque car, «si nous savons faire silence en nous, nous pouvons sentir le sol qui nous a jusqu'ici portés vibrer sous le galop accéléré d'un temps qui se précipite», et comprendre que nous nous condamnons à vivre entassés dans un «univers concentrationnaire surpeuplé et surorganisé» (le terme concentrationnaire est de nouveau employé à la page 31, puis à la page 50), où l'espace à l'évidence mais aussi le temps nous manqueront, alors que nous nous disperserons «dans un vide illimité, dépourvu de bornes matérielles, autant que spirituelles».  Hélas, l'homme moderne ne semble avoir de goût, comme le pensait Max Picard, que pour la fuite et, fuyant sans cesse, il semble précipiter la création entière dans sa propre vitesse s'accroissant davantage, la fuite appelant la fuite, bien qu'il ne faille pas confondre cette accélération avec le «rythme d'une existence humaine [qui] est celui d'une tragédie dont le dénouement se précipite». Ainsi, la «nuit d'amour dont l'aube semblait ne jamais devoir se lever n'est plus qu'un bref instant de rêve entre le jour et le jour; du printemps au printemps, les saisons sont plus courtes que ne l'étaient les heures. Vient même un âge qui réalise la disparition du présent, qui ne peut plus dire : je vis, mais : j'ai vécu; où rien n'est sûr, sinon que tout est déjà fini» (p. 22).

Hélas, l'homme moderne ne semble avoir de goût, comme le pensait Max Picard, que pour la fuite et, fuyant sans cesse, il semble précipiter la création entière dans sa propre vitesse s'accroissant davantage, la fuite appelant la fuite, bien qu'il ne faille pas confondre cette accélération avec le «rythme d'une existence humaine [qui] est celui d'une tragédie dont le dénouement se précipite». Ainsi, la «nuit d'amour dont l'aube semblait ne jamais devoir se lever n'est plus qu'un bref instant de rêve entre le jour et le jour; du printemps au printemps, les saisons sont plus courtes que ne l'étaient les heures. Vient même un âge qui réalise la disparition du présent, qui ne peut plus dire : je vis, mais : j'ai vécu; où rien n'est sûr, sinon que tout est déjà fini» (p. 22).

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Acheter

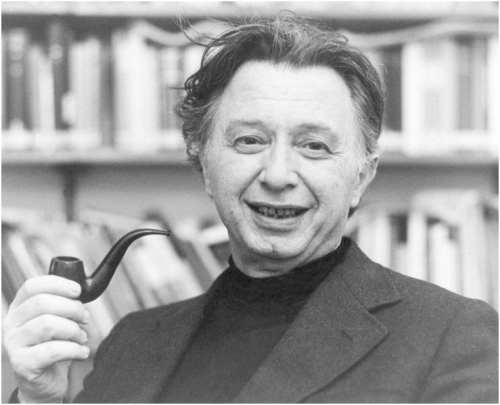

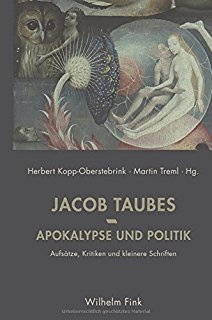

Acheter  Évidemment, tout, absolument tout étant lié, surtout lorsqu'il s'agit des affinités électives existant entre les grands esprits qui appréhendent le monde en établissant des arches, parfois fragiles mais stupéfiantes de hardiesse, entre des réalités qu'en apparence rien ne relie (cf. p. 38), je ne pouvais, poursuivant la lecture de cet excellent petit livre qui m'a fait découvrir le fulgurant (et, apparemment, horripilant) Jacob Taubes, que finalement tomber sur le nom qui, selon ce dernier, reliait Maritain à Schmitt, qualifié de «profond penseur catholique» : Léon Bloy, autrement dit le porteur, le garnt ou, pourquoi pas, le «signe secret» (p. 96) lui-même. Après Kafka saluant le génie de l'imprécation bloyenne, c'est au tour du surprenant Taubes, au détour de quelques mots laissés sans la moindre explication, comme l'une de ces saillies propres aux interventions orales, qui stupéfièrent ou scandalisèrent et pourquoi pas stupéfièrent et scandalisèrent) celles et ceux qui, dans le public, écoutèrent ces maîtres de la parole que furent Taubes et Kojève (cf. p. 47). Il n'aura évidemment échappé à personne que l'un et l'autre, Kafka et le grand commentateur de la Lettre aux Romains de l'apôtre Paul, sont juifs, Jacob Taubes se déclarant même «Erzjude» «archijuif», traduction préférable à celle de «juif au plus profond» (p. 67) que donne notre petit livre : «l'ombre de l'antisémitisme actif se profilait sur notre relation, fragile comme toujours» (p. 47), écrit ainsi l'auteur en évoquant la figure de Carl Schmitt qui, comme Martin Heidegger mais aussi Adolf Hitler, est un «catholique éventé» dont le «génie du ressentiment» lui a permis de lire «les sources à neuf» (p. 112).

Évidemment, tout, absolument tout étant lié, surtout lorsqu'il s'agit des affinités électives existant entre les grands esprits qui appréhendent le monde en établissant des arches, parfois fragiles mais stupéfiantes de hardiesse, entre des réalités qu'en apparence rien ne relie (cf. p. 38), je ne pouvais, poursuivant la lecture de cet excellent petit livre qui m'a fait découvrir le fulgurant (et, apparemment, horripilant) Jacob Taubes, que finalement tomber sur le nom qui, selon ce dernier, reliait Maritain à Schmitt, qualifié de «profond penseur catholique» : Léon Bloy, autrement dit le porteur, le garnt ou, pourquoi pas, le «signe secret» (p. 96) lui-même. Après Kafka saluant le génie de l'imprécation bloyenne, c'est au tour du surprenant Taubes, au détour de quelques mots laissés sans la moindre explication, comme l'une de ces saillies propres aux interventions orales, qui stupéfièrent ou scandalisèrent et pourquoi pas stupéfièrent et scandalisèrent) celles et ceux qui, dans le public, écoutèrent ces maîtres de la parole que furent Taubes et Kojève (cf. p. 47). Il n'aura évidemment échappé à personne que l'un et l'autre, Kafka et le grand commentateur de la Lettre aux Romains de l'apôtre Paul, sont juifs, Jacob Taubes se déclarant même «Erzjude» «archijuif», traduction préférable à celle de «juif au plus profond» (p. 67) que donne notre petit livre : «l'ombre de l'antisémitisme actif se profilait sur notre relation, fragile comme toujours» (p. 47), écrit ainsi l'auteur en évoquant la figure de Carl Schmitt qui, comme Martin Heidegger mais aussi Adolf Hitler, est un «catholique éventé» dont le «génie du ressentiment» lui a permis de lire «les sources à neuf» (p. 112). C'est l'importance, capitale, de cette thématique que Jacob Taubes évoque lorsqu'il affirme que les écailles lui sont tombées des yeux quand il a lu «la courbe tracée par Löwith de Hegel à Nietzsche en passant par Marx et Kierkegaard» (p. 27), auteurs (Hegel, Marx et Kierkegaard) qu'il ne manquera pas d'évoquer dans son Eschatologie occidentale (Nietzsche l'étant dans sa Théologie politique de Paul) en expliquant leur philosophie par l'apocalyptique souterraine qui n'a à vrai dire jamais cessé d'irriguer le monde (4) dans ses multiples transformations, et paraît même s'être orientée, avec le régime nazi, vers une furie de destruction du peuple juif, soit ce peuple élu jalousé par le catholiques (et même les chrétiens) conséquents. Lisons l'explication de Taubes, qui pourra paraître une réduction aux yeux de ses adversaires ou une fulgurance dans l'esprit de ses admirateurs : «Carl Schmitt était membre du Reich allemand avec ses prétentions au Salut», tandis que lui, Taubes, était «fils du peuple véritablement élu par Dieu, suscitant donc l'envie des nations apocalyptiques, une envie qui donne naissance à des fantasmagories et conteste le droit de vivre au peuple réellement élu» (pp. 48-9, le passage plus haut cité suit immédiatement ces lignes).

C'est l'importance, capitale, de cette thématique que Jacob Taubes évoque lorsqu'il affirme que les écailles lui sont tombées des yeux quand il a lu «la courbe tracée par Löwith de Hegel à Nietzsche en passant par Marx et Kierkegaard» (p. 27), auteurs (Hegel, Marx et Kierkegaard) qu'il ne manquera pas d'évoquer dans son Eschatologie occidentale (Nietzsche l'étant dans sa Théologie politique de Paul) en expliquant leur philosophie par l'apocalyptique souterraine qui n'a à vrai dire jamais cessé d'irriguer le monde (4) dans ses multiples transformations, et paraît même s'être orientée, avec le régime nazi, vers une furie de destruction du peuple juif, soit ce peuple élu jalousé par le catholiques (et même les chrétiens) conséquents. Lisons l'explication de Taubes, qui pourra paraître une réduction aux yeux de ses adversaires ou une fulgurance dans l'esprit de ses admirateurs : «Carl Schmitt était membre du Reich allemand avec ses prétentions au Salut», tandis que lui, Taubes, était «fils du peuple véritablement élu par Dieu, suscitant donc l'envie des nations apocalyptiques, une envie qui donne naissance à des fantasmagories et conteste le droit de vivre au peuple réellement élu» (pp. 48-9, le passage plus haut cité suit immédiatement ces lignes).  Cette complexité se retrouve dans le jugement de Jacob Taubes sur Carl Schmitt qui, ce point au moins est évident, avait une réelle importance intellectuelle à ses yeux, était peut-être même l'un des seuls contemporains pour lequel il témoigna de l'estime, au-delà même du fossé qui les séparait : «On vous fait réciter un alphabet démocratique, et tout privat-docent en politologie est évidemment obligé, dans sa leçon inaugurale, de flanquer un coup de pied au cul à Carl Schmitt en disant que la catégorie ami / ennemi n'est pas la bonne. Toute une science s'est édifiée là pour étouffer le problème» (p. 115), problème qui seul compte, et qui, toujours selon Jacob Taubes, a été correctement posé par le seul Carl Schmitt, problème qui n'est autre que l'existence d'une «guerre civile en cours à l'échelle mondiale» (p. 109). Dans sa belle préface, Elettra Stimilli a du reste parfaitement raison de rapprocher, de façon intime, les pensées de Schmitt et de Taubes, écrivant : «Révolution et contre-révolution ont toujours évolué sur le plan linéaire du temps, l'une du point de vue du progrès, l'autre de celui de la tradition. Toutes deux sont liées par l'idée d'un commencement qui, depuis l'époque romaine, est essentiellement une «fondation». Si du côté de la tradition cela ne peut qu'être évident, étant donné que déjà le noyau central de la politique romaine est la foi dans la sacralité de la fondation, entendue comme ce qui maintient un lien entre toutes les générations futures et doit pour cette raison être transmise, par ailleurs, nous ne parviendrons pas à comprendre les révolutions de l'Occident moderne dans leur grandeur et leur tragédie si, comme le dit Hannah Arendt, nous ne le concevons pas comme «autant d'efforts titanesques accomplis pour reconstruire les bases, renouer le fil interrompu de la tradition et restaurer, avec la fondation de nouveaux systèmes politiques, ce qui pendant tant de siècles a conféré dignité et grandeur aux affaires humaines» (pp. 15-6).

Cette complexité se retrouve dans le jugement de Jacob Taubes sur Carl Schmitt qui, ce point au moins est évident, avait une réelle importance intellectuelle à ses yeux, était peut-être même l'un des seuls contemporains pour lequel il témoigna de l'estime, au-delà même du fossé qui les séparait : «On vous fait réciter un alphabet démocratique, et tout privat-docent en politologie est évidemment obligé, dans sa leçon inaugurale, de flanquer un coup de pied au cul à Carl Schmitt en disant que la catégorie ami / ennemi n'est pas la bonne. Toute une science s'est édifiée là pour étouffer le problème» (p. 115), problème qui seul compte, et qui, toujours selon Jacob Taubes, a été correctement posé par le seul Carl Schmitt, problème qui n'est autre que l'existence d'une «guerre civile en cours à l'échelle mondiale» (p. 109). Dans sa belle préface, Elettra Stimilli a du reste parfaitement raison de rapprocher, de façon intime, les pensées de Schmitt et de Taubes, écrivant : «Révolution et contre-révolution ont toujours évolué sur le plan linéaire du temps, l'une du point de vue du progrès, l'autre de celui de la tradition. Toutes deux sont liées par l'idée d'un commencement qui, depuis l'époque romaine, est essentiellement une «fondation». Si du côté de la tradition cela ne peut qu'être évident, étant donné que déjà le noyau central de la politique romaine est la foi dans la sacralité de la fondation, entendue comme ce qui maintient un lien entre toutes les générations futures et doit pour cette raison être transmise, par ailleurs, nous ne parviendrons pas à comprendre les révolutions de l'Occident moderne dans leur grandeur et leur tragédie si, comme le dit Hannah Arendt, nous ne le concevons pas comme «autant d'efforts titanesques accomplis pour reconstruire les bases, renouer le fil interrompu de la tradition et restaurer, avec la fondation de nouveaux systèmes politiques, ce qui pendant tant de siècles a conféré dignité et grandeur aux affaires humaines» (pp. 15-6).

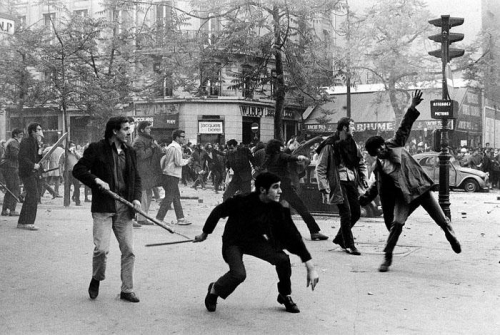

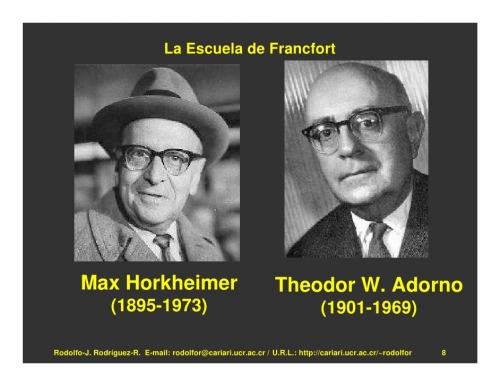

However, the Frankfurt School suggested a different road to the communist paradise than that chosen by Lenin and Stalin in Soviet Russia. The direct intellectual precursors of the Frankfurt School, the Italian Antonio Gramsci (1891 – 1937) and the Hungarian Georg Lukács (1885 – 1971) (photo), had recognized that further west in Europe there was an obstacle on this path which could not be eliminated by physical violence and terror: the private, middle class, classical liberal bourgeois culture based on Christian values. These, they concluded, needed to be destroyed by infiltration of the institutions. Their followers have succeeded in doing so. The sorcerer's apprentices of the Frankfurt School conjured up an army of hobgoblins who empty their buckets over us every day. Instead of water, the buckets are filled with what Lukács had approvingly labelled ‘cultural terrorism.’

However, the Frankfurt School suggested a different road to the communist paradise than that chosen by Lenin and Stalin in Soviet Russia. The direct intellectual precursors of the Frankfurt School, the Italian Antonio Gramsci (1891 – 1937) and the Hungarian Georg Lukács (1885 – 1971) (photo), had recognized that further west in Europe there was an obstacle on this path which could not be eliminated by physical violence and terror: the private, middle class, classical liberal bourgeois culture based on Christian values. These, they concluded, needed to be destroyed by infiltration of the institutions. Their followers have succeeded in doing so. The sorcerer's apprentices of the Frankfurt School conjured up an army of hobgoblins who empty their buckets over us every day. Instead of water, the buckets are filled with what Lukács had approvingly labelled ‘cultural terrorism.’ The sorcerer's apprentices of the Frankfurt School dreamt of a communist paradise on earth. Initially, among the hard left they were the only ones aware of the fact that this brutal path to paradise would fail. With the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961, however, this failure was obvious to all. This was the New Left’s moment. It was only then that they got any traction and noticeable response. At least in Western Europe. In the US, this moment of truth may have come a little later. Gary North contends in his book ‘Unholy Spirits’ that John F. Kennedy’s death was “the death rattle of the older rationalism.” A few weeks later, Beatlemania came to America. However, the appearance of the book ‘Silent Spring’ by Rachel Carson in September 1962, which heralded the start of environmentalism, points to the Berlin Wall as the more fundamental game changer in the West. A few years later, the spellbound hobgoblins began their long march through the institutions.

The sorcerer's apprentices of the Frankfurt School dreamt of a communist paradise on earth. Initially, among the hard left they were the only ones aware of the fact that this brutal path to paradise would fail. With the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961, however, this failure was obvious to all. This was the New Left’s moment. It was only then that they got any traction and noticeable response. At least in Western Europe. In the US, this moment of truth may have come a little later. Gary North contends in his book ‘Unholy Spirits’ that John F. Kennedy’s death was “the death rattle of the older rationalism.” A few weeks later, Beatlemania came to America. However, the appearance of the book ‘Silent Spring’ by Rachel Carson in September 1962, which heralded the start of environmentalism, points to the Berlin Wall as the more fundamental game changer in the West. A few years later, the spellbound hobgoblins began their long march through the institutions.

Qu’on puisse avoir des doutes ou des réclamations sur un parti comme le Front National est logique, mais la victoire politique doit s’abstenir d’une réaction similaire à celle qui pourrait avoir lieu à la buvette du coin. D’autant plus dans une situation de fait majoritaire où ce parti doit obtenir 50,1% des voix pour réussir. Et cela, aussi bien pour les présidentielles que pour les législatives.

Qu’on puisse avoir des doutes ou des réclamations sur un parti comme le Front National est logique, mais la victoire politique doit s’abstenir d’une réaction similaire à celle qui pourrait avoir lieu à la buvette du coin. D’autant plus dans une situation de fait majoritaire où ce parti doit obtenir 50,1% des voix pour réussir. Et cela, aussi bien pour les présidentielles que pour les législatives.

Commençant par ces conditions préalables, Carl Schmitt développa la théorie de la « guerre totale » et de la « guerre limitée » dénommée « guerre de forme », où la guerre totale est la conséquence de l’idéologie universaliste utopique qui nie les différences culturelles, historiques, étatiques et nationales naturelles entre les peuples. Une telle guerre représente en fait une menace de destruction pour toute l’humanité. Selon Carl Schmitt, l’humanisme extrémiste est la voie directe vers une telle guerre qui entraînerait l’implication non seulement des militaires mais aussi des populations civiles dans un conflit. Ceci est en fin de compte le danger le plus terrible. D’un autre coté, les « guerres de forme » sont inévitables du fait des différences entre les peuples et entre leurs cultures indestructibles. Les « guerres de forme » impliquent la participation de soldats professionnels, et peuvent être régulées par les règles légales définies de l’Europe qui portaient jadis le nom de Jus Publicum Europeum (Loi Commune Européenne). Par conséquent, de telles guerres représentent un moindre mal dont la reconnaissance théorique de leur inévitabilité peut protéger les peuples à l’avance contre un conflit « totalisé » et une « guerre totale ». A ce sujet, on peut citer le fameux paradoxe établi par Chigalev dans Les Possédés de Dostoïevski, qui dit : « En partant de la liberté absolue, j’arrive à l’esclavage absolu ». En paraphrasant cette vérité et en l’appliquant aux idées de Carl Schmitt, on peut dire que les partisans de l’humanisme radical « partent de la paix totale et arrivent à la guerre totale ». Après mûre réflexion, nous pouvons voir l’application de la remarque de Chigalev dans toute l’histoire soviétique. Si les avertissements de Carl Schmitt ne sont pas pris en compte, il sera beaucoup plus difficile de comprendre leur véracité, parce qu’il ne restera plus personne pour attester qu’il avait raison – il ne restera plus rien de l’humanité.

Commençant par ces conditions préalables, Carl Schmitt développa la théorie de la « guerre totale » et de la « guerre limitée » dénommée « guerre de forme », où la guerre totale est la conséquence de l’idéologie universaliste utopique qui nie les différences culturelles, historiques, étatiques et nationales naturelles entre les peuples. Une telle guerre représente en fait une menace de destruction pour toute l’humanité. Selon Carl Schmitt, l’humanisme extrémiste est la voie directe vers une telle guerre qui entraînerait l’implication non seulement des militaires mais aussi des populations civiles dans un conflit. Ceci est en fin de compte le danger le plus terrible. D’un autre coté, les « guerres de forme » sont inévitables du fait des différences entre les peuples et entre leurs cultures indestructibles. Les « guerres de forme » impliquent la participation de soldats professionnels, et peuvent être régulées par les règles légales définies de l’Europe qui portaient jadis le nom de Jus Publicum Europeum (Loi Commune Européenne). Par conséquent, de telles guerres représentent un moindre mal dont la reconnaissance théorique de leur inévitabilité peut protéger les peuples à l’avance contre un conflit « totalisé » et une « guerre totale ». A ce sujet, on peut citer le fameux paradoxe établi par Chigalev dans Les Possédés de Dostoïevski, qui dit : « En partant de la liberté absolue, j’arrive à l’esclavage absolu ». En paraphrasant cette vérité et en l’appliquant aux idées de Carl Schmitt, on peut dire que les partisans de l’humanisme radical « partent de la paix totale et arrivent à la guerre totale ». Après mûre réflexion, nous pouvons voir l’application de la remarque de Chigalev dans toute l’histoire soviétique. Si les avertissements de Carl Schmitt ne sont pas pris en compte, il sera beaucoup plus difficile de comprendre leur véracité, parce qu’il ne restera plus personne pour attester qu’il avait raison – il ne restera plus rien de l’humanité. Le concept de la Décision au sens supra-légal ainsi que la nature même de la Décision elle-même s’accordent avec la théorie du « pouvoir direct » et du « pouvoir indirect » (potestas directa et potestas indirecta). Dans le contexte spécifique de Schmitt, la Décision est prise non seulement dans les instances du « pouvoir direct » (le pouvoir des rois, des empereurs, des présidents, etc.) mais aussi dans les conditions du « pouvoir indirect », dont des exemples peuvent être les organisations religieuses, culturelles ou idéologiques qui influencent l’histoire d’un peuple et d’un Etat, certes pas aussi clairement que les décisions des gouvernants mais qui opèrent néanmoins d’une manière beaucoup plus profonde et formidable. Schmitt pense donc que le « pouvoir indirect » n’est pas toujours négatif, mais d’un autre coté il ne fait qu’une allusion implicite au fait qu’une décision contraire à la volonté du peuple est le plus souvent adoptée et mise en œuvre par de tels moyens de « pouvoir indirect ». Dans son livre Théologie politique et dans sa suite Théologie politique II, il examine la logique du fonctionnement de ces deux types d’autorité dans les Etats et les nations.

Le concept de la Décision au sens supra-légal ainsi que la nature même de la Décision elle-même s’accordent avec la théorie du « pouvoir direct » et du « pouvoir indirect » (potestas directa et potestas indirecta). Dans le contexte spécifique de Schmitt, la Décision est prise non seulement dans les instances du « pouvoir direct » (le pouvoir des rois, des empereurs, des présidents, etc.) mais aussi dans les conditions du « pouvoir indirect », dont des exemples peuvent être les organisations religieuses, culturelles ou idéologiques qui influencent l’histoire d’un peuple et d’un Etat, certes pas aussi clairement que les décisions des gouvernants mais qui opèrent néanmoins d’une manière beaucoup plus profonde et formidable. Schmitt pense donc que le « pouvoir indirect » n’est pas toujours négatif, mais d’un autre coté il ne fait qu’une allusion implicite au fait qu’une décision contraire à la volonté du peuple est le plus souvent adoptée et mise en œuvre par de tels moyens de « pouvoir indirect ». Dans son livre Théologie politique et dans sa suite Théologie politique II, il examine la logique du fonctionnement de ces deux types d’autorité dans les Etats et les nations. Ainsi, l’idée schmittienne du « Grand Espace » possède aussi une dimension spontanée, existentielle et volitionnelle, tout comme le sujet fondamental de l’histoire selon lui, c’est-à-dire le peuple en tant qu’unité politique. Tout comme les géopoliticiens Mackinder et Kjellen, Schmitt opposait les empires thalassocratiques (la Phénicie, l’Angleterre, les Etats-Unis, etc.) aux empires tellurocratiques (l’empire romain, l’empire austro-hongrois, l’empire russe, etc.). Dans cette perspective, l’organisation harmonieuse et organique d’un espace n’est possible que pour les empires tellurocratiques, et la Loi Continentale ne peut être appliquée qu’à eux. La thalassocratie, sortant des limites de son Ile et initiant une expansion navale, entre en conflit avec les tellurocraties et, en accord avec la logique géopolitique, commence à miner diplomatiquement, économiquement et militairement les fondements des « Grands Espaces » continentaux. Ainsi, dans la perspective des « Grands Espaces » continentaux, Schmitt revient une fois de plus aux concepts des paires ennemis/amis et nous/eux, mais cette fois-ci à un niveau planétaire. La volonté des empires continentaux, les « Grands Espaces », se révèle dans la confrontation entre les macro-intérêts continentaux et les macro-intérêts maritimes. La « Mer » défie ainsi la « Terre », et en répondant à ce défi, la « Terre » revient le plus souvent à sa conscience de soi continentale profonde.

Ainsi, l’idée schmittienne du « Grand Espace » possède aussi une dimension spontanée, existentielle et volitionnelle, tout comme le sujet fondamental de l’histoire selon lui, c’est-à-dire le peuple en tant qu’unité politique. Tout comme les géopoliticiens Mackinder et Kjellen, Schmitt opposait les empires thalassocratiques (la Phénicie, l’Angleterre, les Etats-Unis, etc.) aux empires tellurocratiques (l’empire romain, l’empire austro-hongrois, l’empire russe, etc.). Dans cette perspective, l’organisation harmonieuse et organique d’un espace n’est possible que pour les empires tellurocratiques, et la Loi Continentale ne peut être appliquée qu’à eux. La thalassocratie, sortant des limites de son Ile et initiant une expansion navale, entre en conflit avec les tellurocraties et, en accord avec la logique géopolitique, commence à miner diplomatiquement, économiquement et militairement les fondements des « Grands Espaces » continentaux. Ainsi, dans la perspective des « Grands Espaces » continentaux, Schmitt revient une fois de plus aux concepts des paires ennemis/amis et nous/eux, mais cette fois-ci à un niveau planétaire. La volonté des empires continentaux, les « Grands Espaces », se révèle dans la confrontation entre les macro-intérêts continentaux et les macro-intérêts maritimes. La « Mer » défie ainsi la « Terre », et en répondant à ce défi, la « Terre » revient le plus souvent à sa conscience de soi continentale profonde.

Ma réponse sera : le monde conduit par l’économie est le vieux monde. Nous ne regardons pas seulement l’échec misérable des institutions de

Ma réponse sera : le monde conduit par l’économie est le vieux monde. Nous ne regardons pas seulement l’échec misérable des institutions de  Laissez-moi dire quelques mots sur chaque question.

Laissez-moi dire quelques mots sur chaque question. La deuxième hypothèse est que toute société humaine dans le monde entier est à la recherche de développement. C’est aussi un mensonge. En fait, la plupart des communautés indigènes et des confessions religieuses sont organisées contre le développement ; elles n’ont pas de place pour une telle chose dans leur communauté. Près de chez moi, sur la côte ouest de Madagascar, ils brûlent la maison de quiconque devient riche, pour le garder dans la communauté. Ils comprennent très bien que l’argent est le grand fossé entre les êtres humains, et l’économie de marché, la fin des communs. Le fait n’est pas qu’ils sont incapables de se développer eux-mêmes ; la vérité est que, en tant que communauté, ils refusent l’individualisme lié au développement économique. Ils préfèrent leur communauté au droit illimité de rompre avec elle et avec la nature elle-même. La phrase qu’ils préfèrent est « Mieux vaux une touche de fihavanana (le bien-être collectif) qu’une tonne d’or ». Pour le bien de la croissance, ce que nous appelons le développement, c’est la rupture de ces communautés contre leur volonté et la fin de leur bien-être collectif pour les fausses promesses d’un accomplissement individuel. Sous le faux drapeau de la liberté, pour le commerce et l’argent, les Occidentaux l’ont fait à plusieurs reprises, de la rupture du Japon par le

La deuxième hypothèse est que toute société humaine dans le monde entier est à la recherche de développement. C’est aussi un mensonge. En fait, la plupart des communautés indigènes et des confessions religieuses sont organisées contre le développement ; elles n’ont pas de place pour une telle chose dans leur communauté. Près de chez moi, sur la côte ouest de Madagascar, ils brûlent la maison de quiconque devient riche, pour le garder dans la communauté. Ils comprennent très bien que l’argent est le grand fossé entre les êtres humains, et l’économie de marché, la fin des communs. Le fait n’est pas qu’ils sont incapables de se développer eux-mêmes ; la vérité est que, en tant que communauté, ils refusent l’individualisme lié au développement économique. Ils préfèrent leur communauté au droit illimité de rompre avec elle et avec la nature elle-même. La phrase qu’ils préfèrent est « Mieux vaux une touche de fihavanana (le bien-être collectif) qu’une tonne d’or ». Pour le bien de la croissance, ce que nous appelons le développement, c’est la rupture de ces communautés contre leur volonté et la fin de leur bien-être collectif pour les fausses promesses d’un accomplissement individuel. Sous le faux drapeau de la liberté, pour le commerce et l’argent, les Occidentaux l’ont fait à plusieurs reprises, de la rupture du Japon par le  En disant cela, nous sommes proches du grand secret caché derrière la scène ; nous sommes confrontés à la fin des systèmes libéraux tels que nous les connaissions.

En disant cela, nous sommes proches du grand secret caché derrière la scène ; nous sommes confrontés à la fin des systèmes libéraux tels que nous les connaissions. Les biens communs, ou les communs, ne cadrent pas bien avec le libre-échange, la libre circulation des capitaux, les privatisations de masse et l’hypothèse de base que tout est à vendre ; la terre, l’eau douce, l’air et les êtres humains. En fait, le libre-échange et les marchés mondiaux sont les pires ennemis des communs. La grande ouverture des dernières communautés vivant sur elles-mêmes est une condamnation à mort. Bienvenue à la réinvention de l’esclavage par ces apôtres des migrations de masse et des frontières ouvertes ! Je n’ai aucun doute à ce sujet ; une grande partie de ce que nous appelons « développement » et « aide internationale » sera bientôt considérée comme un crime contre l’humanité – l’effondrement des biens communs pour le bénéfice des entreprises mondialisées et des intérêts privés. Et le mouvement des « no borders » sera également considéré comme une manière subtile d’utiliser le travail forcé et embaucher des esclaves avec un double avantage : premièrement, faire le bien avec le sentiment d’être d’une qualité morale supérieure, deuxièmement, faire du bien à la

Les biens communs, ou les communs, ne cadrent pas bien avec le libre-échange, la libre circulation des capitaux, les privatisations de masse et l’hypothèse de base que tout est à vendre ; la terre, l’eau douce, l’air et les êtres humains. En fait, le libre-échange et les marchés mondiaux sont les pires ennemis des communs. La grande ouverture des dernières communautés vivant sur elles-mêmes est une condamnation à mort. Bienvenue à la réinvention de l’esclavage par ces apôtres des migrations de masse et des frontières ouvertes ! Je n’ai aucun doute à ce sujet ; une grande partie de ce que nous appelons « développement » et « aide internationale » sera bientôt considérée comme un crime contre l’humanité – l’effondrement des biens communs pour le bénéfice des entreprises mondialisées et des intérêts privés. Et le mouvement des « no borders » sera également considéré comme une manière subtile d’utiliser le travail forcé et embaucher des esclaves avec un double avantage : premièrement, faire le bien avec le sentiment d’être d’une qualité morale supérieure, deuxièmement, faire du bien à la

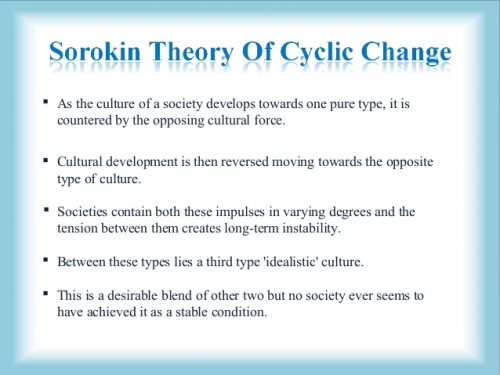

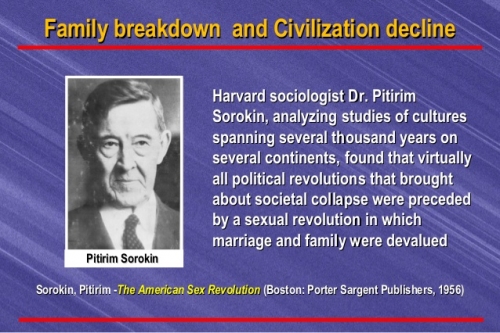

While many living in the West of Sorokin’s day didn’t clearly apprehend what was happening, Sorokin said, they harbored “at least a vague feeling that the issue is not merely that of ‘prosperity,’ or ‘democracy,’ or ‘capitalism’”—in other words, matters handled through normal politics and political action. “The organism of the Western society and culture seems to be undergoing one of the deepest and most significant crises of its life. The crisis is far greater than the ordinary; its depth is unfathomable, its end not yet in sight, and the whole of the Western society is involved in it,” Sorokin wrote in Social and Cultural Dynamics, his 1937 masterwork, whose themes he elaborated upon in subsequent volumes, books and essays.

While many living in the West of Sorokin’s day didn’t clearly apprehend what was happening, Sorokin said, they harbored “at least a vague feeling that the issue is not merely that of ‘prosperity,’ or ‘democracy,’ or ‘capitalism’”—in other words, matters handled through normal politics and political action. “The organism of the Western society and culture seems to be undergoing one of the deepest and most significant crises of its life. The crisis is far greater than the ordinary; its depth is unfathomable, its end not yet in sight, and the whole of the Western society is involved in it,” Sorokin wrote in Social and Cultural Dynamics, his 1937 masterwork, whose themes he elaborated upon in subsequent volumes, books and essays. Appealing both to cultural conservatives and New Age spiritualists (Sorokin saw yoga as a means of integrating spirit and intellect), he attracted the attention of Albert Einstein, Herbert Hoover, and John F. Kennedy. His predictive powers were formidable, and contemporary figures took heed. When he died in 1968, he remained an illustrious, well-known figure, and his opinions were widely written about and explored. Since then, however, he has receded from memory.

Appealing both to cultural conservatives and New Age spiritualists (Sorokin saw yoga as a means of integrating spirit and intellect), he attracted the attention of Albert Einstein, Herbert Hoover, and John F. Kennedy. His predictive powers were formidable, and contemporary figures took heed. When he died in 1968, he remained an illustrious, well-known figure, and his opinions were widely written about and explored. Since then, however, he has receded from memory.

Aristide Leucate propose surtout la biographie intellectuelle d’un des plus grands penseurs du XXe siècle. Juriste de formation, universitaire de haut vol, Carl Schmitt est un Prussien de l’Ouest en référence à ces terres rhénanes remises à la Prusse par le traité de Vienne en 1814 – 1815. Francophone et latiniste, ce catholique intransigeant admira toujours l’Espagne et tout particulièrement son Âge d’Or. Il n’est pas fortuit si sa fille unique, Amina, épousa en 1957 un professeur de droit de nationalité espagnole, ancien membre de la Phalange, Alfonso Otero Varela. Ses quatre petits-enfants sont donc des citoyens espagnols.

Aristide Leucate propose surtout la biographie intellectuelle d’un des plus grands penseurs du XXe siècle. Juriste de formation, universitaire de haut vol, Carl Schmitt est un Prussien de l’Ouest en référence à ces terres rhénanes remises à la Prusse par le traité de Vienne en 1814 – 1815. Francophone et latiniste, ce catholique intransigeant admira toujours l’Espagne et tout particulièrement son Âge d’Or. Il n’est pas fortuit si sa fille unique, Amina, épousa en 1957 un professeur de droit de nationalité espagnole, ancien membre de la Phalange, Alfonso Otero Varela. Ses quatre petits-enfants sont donc des citoyens espagnols.

L’on voit l’importance déterminante que Kunstler attribue à un courant philosophique bien connu, celui que l’on connaît sous divers noms dont celui de “déconstruction”. Le nom de Jacques Derrida y figure en bonne place et il nous a semblé ainsi particulièrement opportun de revenir sur un texte F&C (

L’on voit l’importance déterminante que Kunstler attribue à un courant philosophique bien connu, celui que l’on connaît sous divers noms dont celui de “déconstruction”. Le nom de Jacques Derrida y figure en bonne place et il nous a semblé ainsi particulièrement opportun de revenir sur un texte F&C (

Ainsi revenons-nous au drame de Derrida que restituent les quelques minutes de confidences qu’on a écoutées. Ayant écarté les occurrences sociales et autres qui figurent au début des confidences, nous revenons au plus profond du secret de l’être, pour considérer enfin ce qu’il nous dit en vérité, selon notre interprétation. Dans ces moments de semi-conscience que lui-même (Derrida) qualifie de la plus grande “vigilance”, c’est-à-dire de la lucidité qui dit “la vérité” en écartant l’espèce d’opium de la pure spéculation intellectuelle, l’esprit qui fait “ce qui doit être fait” est confronté à ce jugement terrible : « Ce que tu viens de faire est i-na-dmi-ssible »... Non pas “selon ta fonction, ta position sociale, ton respect de la hiérarchie”, mais parce qu’il s’agit de quelque chose d’“i-na-dmi-ssible” en soi, – et cela ne peut être alors que le fait de céder à la tentation épouvantable, de succomber à l’influence du Mal, d’accepter le simulacre qu’il impose.

Ainsi revenons-nous au drame de Derrida que restituent les quelques minutes de confidences qu’on a écoutées. Ayant écarté les occurrences sociales et autres qui figurent au début des confidences, nous revenons au plus profond du secret de l’être, pour considérer enfin ce qu’il nous dit en vérité, selon notre interprétation. Dans ces moments de semi-conscience que lui-même (Derrida) qualifie de la plus grande “vigilance”, c’est-à-dire de la lucidité qui dit “la vérité” en écartant l’espèce d’opium de la pure spéculation intellectuelle, l’esprit qui fait “ce qui doit être fait” est confronté à ce jugement terrible : « Ce que tu viens de faire est i-na-dmi-ssible »... Non pas “selon ta fonction, ta position sociale, ton respect de la hiérarchie”, mais parce qu’il s’agit de quelque chose d’“i-na-dmi-ssible” en soi, – et cela ne peut être alors que le fait de céder à la tentation épouvantable, de succomber à l’influence du Mal, d’accepter le simulacre qu’il impose.

Les philosophes de la French Theory eurent un peu le même effet que celui qu’amena Sigmund Freud en le pressentant largement, lors de son premier voyage aux USA en 1909, lorsqu’il s’exclama que ce pays-continent était la terre rêvée pour la psychanalyse tant il était producteur fondamental de la névrose caractéristique de la modernité, désignée en 1879 par le Dr. Beard comme “

Les philosophes de la French Theory eurent un peu le même effet que celui qu’amena Sigmund Freud en le pressentant largement, lors de son premier voyage aux USA en 1909, lorsqu’il s’exclama que ce pays-continent était la terre rêvée pour la psychanalyse tant il était producteur fondamental de la névrose caractéristique de la modernité, désignée en 1879 par le Dr. Beard comme “

L’on parlera de réussites individuelles, ou de succès statistiques « d’apprenants » dans les examens généraux de fin d’études – mot absurde puisqu’il n ‘y aura pas eu de vrai commencement et de fondation assurée -, et de carrières, mais que vaut un savoir au sein d’une nation ou d’une nature de peuple fragilisée, et ignorant qu’elle porte en elle un destin, lequel la broiera si elle ne le maîtrise ? Cette question s’est posée au professeur Heidegger, le terme de professeur étant plus proche de la profession de foi que de l’exercice mécanique de répétitions vides, brillantes mais infécondes, comme une coque de noix vide.

L’on parlera de réussites individuelles, ou de succès statistiques « d’apprenants » dans les examens généraux de fin d’études – mot absurde puisqu’il n ‘y aura pas eu de vrai commencement et de fondation assurée -, et de carrières, mais que vaut un savoir au sein d’une nation ou d’une nature de peuple fragilisée, et ignorant qu’elle porte en elle un destin, lequel la broiera si elle ne le maîtrise ? Cette question s’est posée au professeur Heidegger, le terme de professeur étant plus proche de la profession de foi que de l’exercice mécanique de répétitions vides, brillantes mais infécondes, comme une coque de noix vide.

Chacun de ces « présupposés » fait l’objet d’analyses minutieuses. L’Essence du politique est un livre dense, mais clair et bien écrit. La pensée ne se dérobe jamais derrière un échafaudage de termes abscons. Si l’on prend l’exemple du troisième présupposé, Freund montra que non seulement l’ennemi est impossible à supprimer, mais encore qu’il est nécessaire pour donner une existence politique à un peuple, développant ainsi l’intuition de Saint-Exupéry : « L’ennemi te limite donc, te donne ta forme et te fonde » (Citadelle).

Chacun de ces « présupposés » fait l’objet d’analyses minutieuses. L’Essence du politique est un livre dense, mais clair et bien écrit. La pensée ne se dérobe jamais derrière un échafaudage de termes abscons. Si l’on prend l’exemple du troisième présupposé, Freund montra que non seulement l’ennemi est impossible à supprimer, mais encore qu’il est nécessaire pour donner une existence politique à un peuple, développant ainsi l’intuition de Saint-Exupéry : « L’ennemi te limite donc, te donne ta forme et te fonde » (Citadelle).

Dans son texte, « Le retour de la vraie Droite », l’auteur revient en premier lieu sur l’ascension culturelle de la Gauche et conqtate que « les idéaux de l’Occident ont subi une inversion totale, et des idées qui se situaient initialement à la périphérie de l’extrême gauche ont été élevées au rang de normes sociales qui prévalent aujourd’hui dans l’éducation, les médias, les institutions gouvernementales et les ONG privées (p. 2) ». Un tel résultat, nous explique l’auteur, n’aurait pas pu être possible sans « les sociologues et philosophes marxistes de l’Institut für Sozialforschung de Francfort [qui], au début du XXe siècle, visaient, au travers de la conception de la philosophie et leur analyse sociale sélective, à saper la confiance dans les valeurs et hiérarchies traditionnelles (p. 2) ». Sans doute que d’autres facteurs sont rentrés en ligne de compte concernant l’involution de l’Occident, et non pas uniquement des facteurs politiques, mais cela ne rentre peut-être pas dans la grille de lecture de l’auteur – ce qui n’enlève rien, par ailleurs, à la justesse de ses propos.

Dans son texte, « Le retour de la vraie Droite », l’auteur revient en premier lieu sur l’ascension culturelle de la Gauche et conqtate que « les idéaux de l’Occident ont subi une inversion totale, et des idées qui se situaient initialement à la périphérie de l’extrême gauche ont été élevées au rang de normes sociales qui prévalent aujourd’hui dans l’éducation, les médias, les institutions gouvernementales et les ONG privées (p. 2) ». Un tel résultat, nous explique l’auteur, n’aurait pas pu être possible sans « les sociologues et philosophes marxistes de l’Institut für Sozialforschung de Francfort [qui], au début du XXe siècle, visaient, au travers de la conception de la philosophie et leur analyse sociale sélective, à saper la confiance dans les valeurs et hiérarchies traditionnelles (p. 2) ». Sans doute que d’autres facteurs sont rentrés en ligne de compte concernant l’involution de l’Occident, et non pas uniquement des facteurs politiques, mais cela ne rentre peut-être pas dans la grille de lecture de l’auteur – ce qui n’enlève rien, par ailleurs, à la justesse de ses propos.

Francisco de Vitoria (environ 1483–1546), un autre représentant de cette école, a en outre souligné la nature sociale axée sur la communauté des êtres humains qui les conduit à se regrouper volontairement en communautés. L’Etat est donc le mode d’existence le plus adapté à la nature de l’être humain. Au sein de cette communauté, l’individu peut perfectionner ses capacités, échanger avec les autres et pratiquer l’entraide. Troxler remarquait à ce propos que «la politique est la réconciliation de l’individu avec le monde».33

Francisco de Vitoria (environ 1483–1546), un autre représentant de cette école, a en outre souligné la nature sociale axée sur la communauté des êtres humains qui les conduit à se regrouper volontairement en communautés. L’Etat est donc le mode d’existence le plus adapté à la nature de l’être humain. Au sein de cette communauté, l’individu peut perfectionner ses capacités, échanger avec les autres et pratiquer l’entraide. Troxler remarquait à ce propos que «la politique est la réconciliation de l’individu avec le monde».33

L’ouvrage est essentiel car depuis le délire a débordé des campus et gagné la société occidentale toute entière. En même temps qu’elle déboulonne les statues, remet en cause le sexe de Dieu et diabolise notre héritage littéraire et culturel, cette société intégriste-sociétale donc menace le monde libre russe, chinois ou musulman (je ne pense pas à Riyad…) qui contrevient à son alacrité intellectuelle. Produit d’un nihilisme néo-nietzschéen, de l’égalitarisme démocratique et aussi de l’ennui des routines intellos (Bloom explique qu’on voulait « débloquer des préjugés, « trouver du nouveau »), la pensée politiquement correcte va tout dévaster comme un feu de forêt de Stockholm à Barcelone et de Londres à Berlin. On va dissoudre les nations et la famille (ou ce qu’il en reste), réduire le monde en cendres au nom du politiquement correct avant d’accueillir dans les larmes un bon milliard de réfugiés. Bloom pointe notre lâcheté dans tout ce processus, celle des responsables et l’indifférence de la masse comme toujours.

L’ouvrage est essentiel car depuis le délire a débordé des campus et gagné la société occidentale toute entière. En même temps qu’elle déboulonne les statues, remet en cause le sexe de Dieu et diabolise notre héritage littéraire et culturel, cette société intégriste-sociétale donc menace le monde libre russe, chinois ou musulman (je ne pense pas à Riyad…) qui contrevient à son alacrité intellectuelle. Produit d’un nihilisme néo-nietzschéen, de l’égalitarisme démocratique et aussi de l’ennui des routines intellos (Bloom explique qu’on voulait « débloquer des préjugés, « trouver du nouveau »), la pensée politiquement correcte va tout dévaster comme un feu de forêt de Stockholm à Barcelone et de Londres à Berlin. On va dissoudre les nations et la famille (ou ce qu’il en reste), réduire le monde en cendres au nom du politiquement correct avant d’accueillir dans les larmes un bon milliard de réfugiés. Bloom pointe notre lâcheté dans tout ce processus, celle des responsables et l’indifférence de la masse comme toujours. Tout cela évoque Henry James mais aussi Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, Scott Fitzgerald, à qui Woody Allen rendait un rare hommage dans son film Minuit à Paris – qui plut à tout le monde, car on remontait à une époque culturelle brillante, non fliquée, censurée. Cette soi-disant « génération perdue » des couillons de la presse n’avait rien à voir avec la nôtre – avec la mienne.

Tout cela évoque Henry James mais aussi Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, Scott Fitzgerald, à qui Woody Allen rendait un rare hommage dans son film Minuit à Paris – qui plut à tout le monde, car on remontait à une époque culturelle brillante, non fliquée, censurée. Cette soi-disant « génération perdue » des couillons de la presse n’avait rien à voir avec la nôtre – avec la mienne.

Recensé : Paulin Ismard,

Recensé : Paulin Ismard,